Carrowmore

The day after our trip to the Keshcorran caves, my brother and I decided to make our way to Carrowmore, Ireland’s largest and oldest megalithic cemetery. Archaeologists estimate the site contains the remains of at least 35 Neolithic passage tombs, constructed as long ago as 4,000 BC, and varying widely in condition. For context megalithic refers to large prehistoric monuments or structures built from stone, while Neolithic relates to the era of their construction. In Ireland, the Neolithic period ranged from 4,000 to 2,500 BC.

Arriving at Carrowmore, we found the site shut for renovations and the gates to the visitor’s centre closed. However, never ones to let a little gate or wall get in the way of a good field trip, it wasn’t long before we found ourselves strolling through lush green fields among the many tombs.

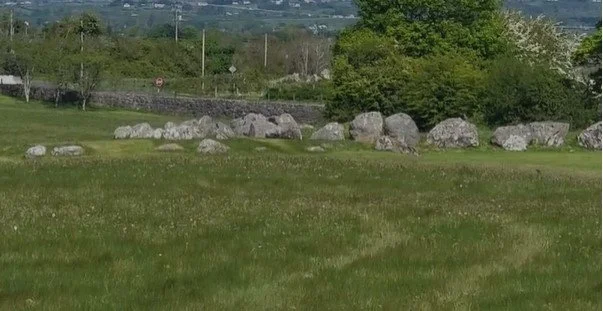

The fields of Carrowmore

Despite being in a literal ancient necropolis, there was nothing ominous about the site, and stumbling across the lower half of what might once have been a rabbit was about as sinister as it got.

As far as the passage graves went, their remains varied from just a few boulders spread out in rough circles, to dolmans, right up to Listoghil, or cairn 51, tens of metres in diameter with a dolman in its centre.

Entering the newly renovated Cairn 51, aka Listoghil

Another striking feature of the area was the surrounding sites. From the plains of Carrowmore, we were surrounded by elevated landmarks, with panoramic views of Benbulbin, the Bricklieve mountains, and of course the Maedbh’s cairn crowned Knocknarea Hill, all clearly visible in the fine weather.

Since all these sites, including the Dartry mountains which Benbulbin is a part of, contain passage grave cairns, it is speculated by some archaeologists that Carrowmore is part of a much wider megalithic necropolis, spanning much of county Sligo.

The Dolman inside Listoghil/Cairn 51

Myths & Legends

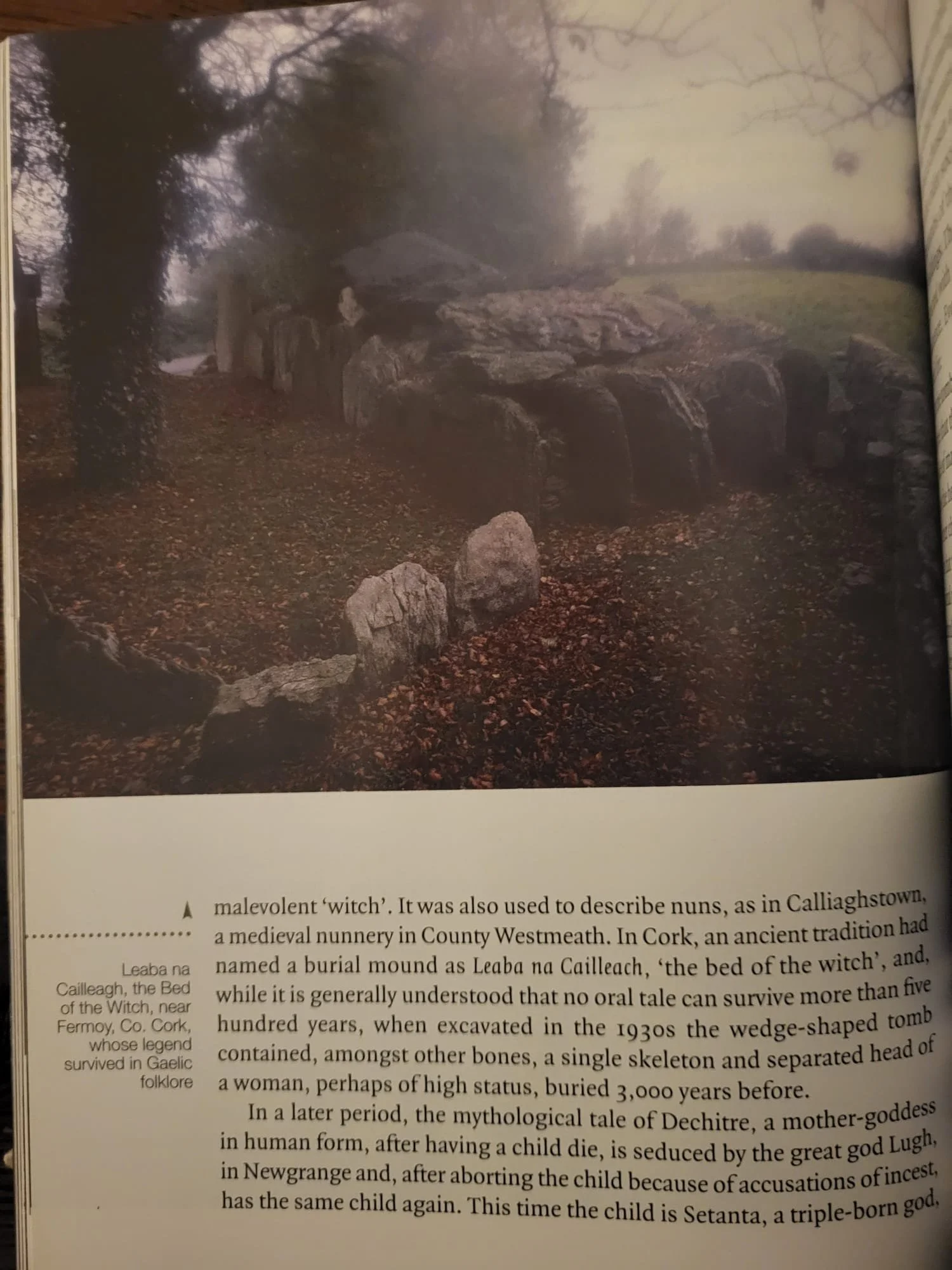

As legends go, the site is associated with the Cailleach, the Irish word for witch or hag. She is thought to have used her magic to shape the landscape. Some historians believe she may have been derived from the goddess Brigid, a member of the Tuath De Danann known for her protective and healing powers, a pagan deity later adopted as a saint by Christian Ireland. Tales of the Cailleach can be found throughout the country, including Loughcrew, in county Meath covered in a previous blog post, and at ‘An Leaba Na Cailleach’ the bed of the witch, outside Fermoy, county Cork.

Description of ‘Leaba Na Cailleach’ extract from Secrets of the Stones by Robert Vance

This vast Neolithic graveyard is also thought to be the final resting place of the Fir Bolg, a race of people defeated in the first battle of Magh Tuiredh by the incoming Tuatha Dé Danann. This is at least according to the ‘Book of Invasions,’ a somewhat mythical account of prehistoric Ireland, documenting its ensuing waves of colonisers, one conquest after another. The Tuatha Dé Danann, a tribe of tall and fair, god-like beings would later find themselves engaged in battle with yet another set of invaders, in the form of the Milesians, the final group of settlers, and ancestors of the Celtic Irish.

Some believe that the beautiful, magical Dé Dananns were connected to Carrowmore, and that its megalithic constructions acted as access points, or portals to their Otherworld, an alternative realm they took to after their conflict with the Milesians. There they became the people of the sidhe (mounds), and were referred to as the Sidhe, and later, their descendants known as the Fae, or Faries in modern Irish folklore.

The Ancient People of Carrowmore

The reality is that the tombs of Carrowmore were raised long before the written word, so a comprehensive understanding of their construction will always remain a mystery to some extent. However, we know enough about their builders, to know that they were a people who venerated their ancestors through ritual, by cremating and burying their dead beneath the structures they so painstakingly took to build.